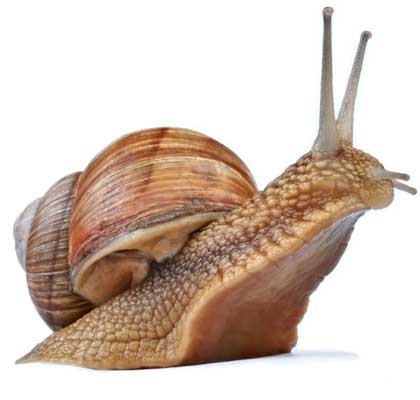

The researchers, from three UK universities, published their report before Christmas in the journal Freshwater Biology. It showed that snails exposed to the smell of predators during the embryonic development stage were better able to avoid those predators after the snails had hatched. They did this both by developing shells that were more protective and by crawling out of dangerous waters.

The question of whether or not to leave the water is an important one for a snail, as it may save it from a predator but carries the risk of desiccation, so getting it right may be literally a matter of life or death. Lead author of the report, Dr Sarah Dalesman of the University of Aberystwyth, expressed surprise at just how well the embryonic snails were able to learn, concluding that this ability might be extremely important in improving the survival chances of the young snails after hatching.

The report also found that embryonic snails that were exposed to a predator smell hatched out smaller, on average, than others that were kept in predator-free conditions. As the report itself notes, this mirrors the effects of stress in the development of mammals, including humans, where foetuses of stressed mothers typically have lower birth weights than others.

One of the key conclusions drawn by the authors is that “embryonic experience may therefore be extremely important in allowing populations to persist”. The opening words of the report, presenting a summary of the key findings, similarly comment that the biology in the very early life stages may – in terms of influencing the dynamics and survival of the population – be as important as, or even more important than, later stages.

So much for snails. What do we know about the ability of unborn humans to learn?

Plenty of studies have demonstrated that memories can be set down before birth, and that these can influence behaviour after birth. One such study (reported in The Independent and Daily Telegraph on 4 April 1995) was carried out by Dr Peter Hepper, then professor of psychology at Queen’s University in Belfast. Dr Hepper was no pro-life advocate, as he was suggesting that his studies could help mothers to make a choice as to whether or not to abort children with Down’s syndrome. His report, though, found that:

- an unborn child can start to learn and remember during the second trimester of the mother’s pregnancy, so between 4 and 6 months;

- from 24 weeks, unborn babies can recognise and remember sounds, and distinguish between those that are important to them and those that are not;

- the unborn baby can recognise his or her mother’s voice from around 30 weeks.

A second report of Dr Hepper’s, this time reported in The Lancet on 11 June 1998, found that babies stopped crying and became more alert when played the theme tune from the Australian soap Neighbours if their mothers had watched the programme during pregnancy.

Two other researchers, from Keele University, found that unborn children could lay down musical memories from the 30th week of pregnancy, and possibly as early as the 20th week, before the cerebral cortex is fully functional .

In 2013, the University of Washington reported that unborn babies start to learn language and, within just hours of birth, can differentiate between sounds from languages to which they have been exposed in the womb and the sounds of other languages .

Moving from sound to smell, a French report, published in 2001, showed that the babies of mothers who ate anise during pregnancy were attracted to the odour after birth, whereas other young babies were either neutral or repelled by the smell .

If snails can learn life-saving skills at the embryonic state, it is hardly surprising that young humans can also start to learn matters of importance before birth. Any internet search will quickly demonstrate a wealth of evidence that the unborn baby can learn – whether speech, music, other sounds, or smell. These studies collectively demonstrate yet again the scientific fact that human development is a continuous process that starts at conception.

Comments on this blog? Email them to johnsmeaton@spuc.org.uk

Sign up for alerts to new blog-posts and/or for SPUC's other email services

Follow SPUC on Twitter

Like SPUC's Facebook Page

Please support SPUC. Please donate, join, and/or leave a legacy